Are drugs for bones a threat to jaws?

Source: Marie McCullough, philly.com

Across the country, dentists have begun asking patients a pointed question before deciding on treatment: Do you take a bone-building medication such as Fosamax?

These widely used drugs, called bisphosphonates, have recently been

linked to a rare side effect that causes parts of the jawbone to

deteriorate and die.

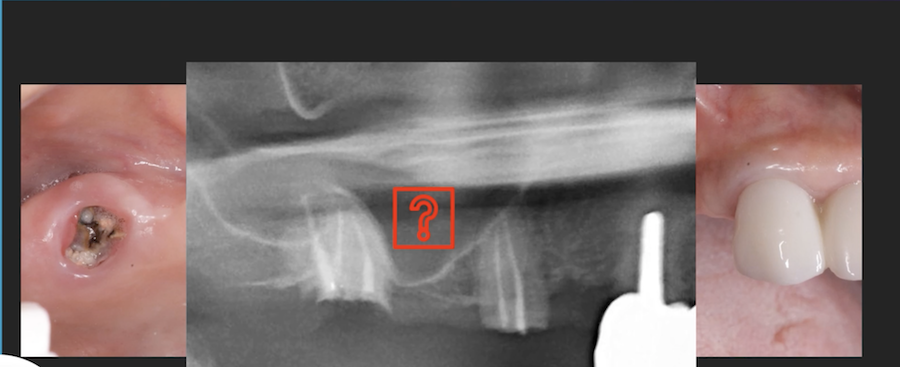

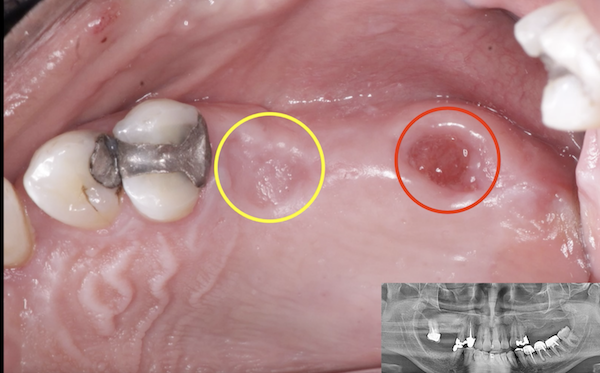

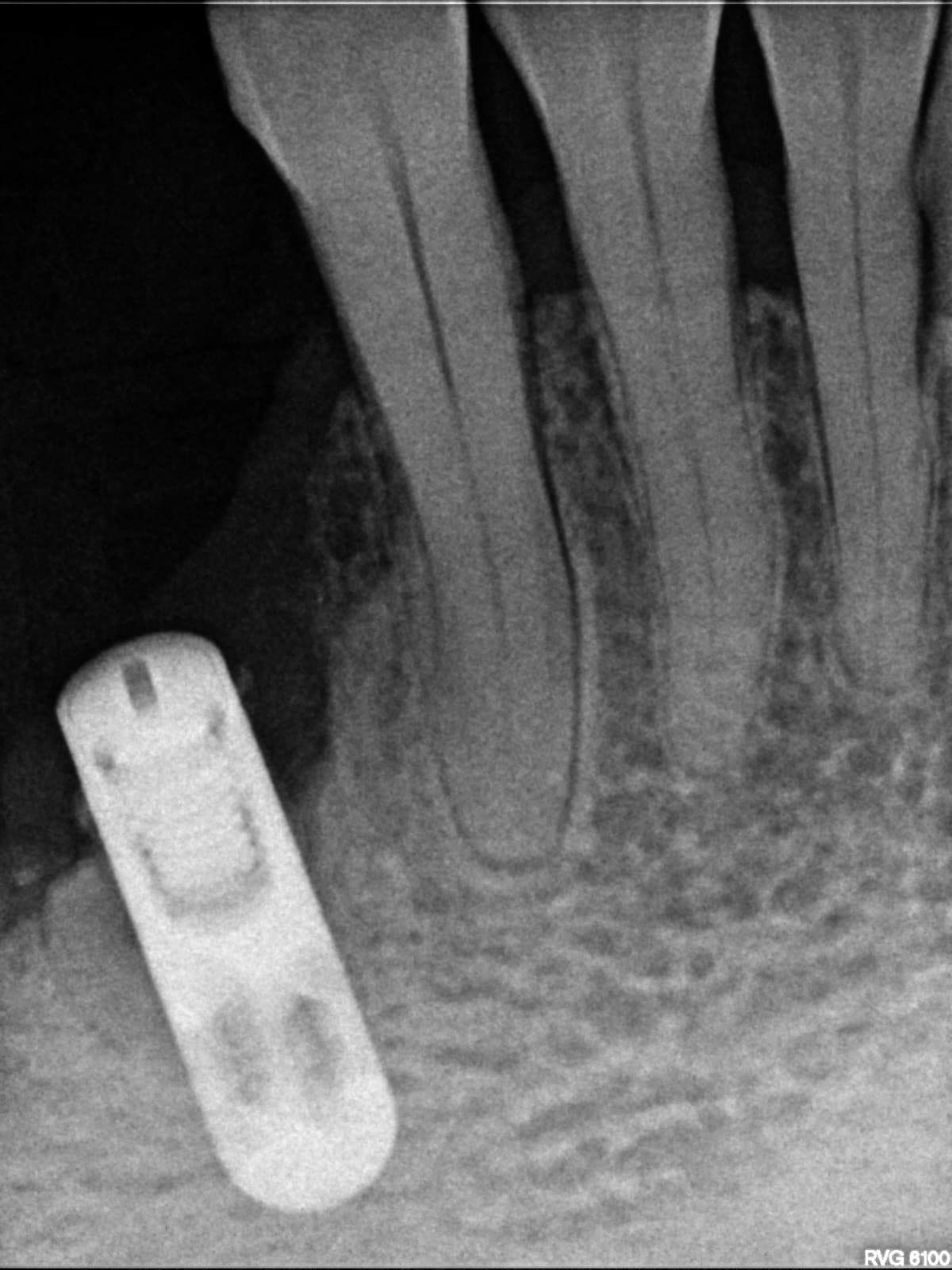

The bulk of the 3,000 published cases of jaw osteonecrosis – meaning

“dead bone” – have occurred after dental procedures, mostly in cancer

patients on intravenous bisphosphonates. But the problem has also

developed out of the blue in otherwise healthy people taking

bisphosphonate pills to boost bone density.

“If you’re going to be on this drug, make sure you really need it,” said Alan Meltzer, a Voorhees periodontist.

Since 2003, when the first 36 cases were described in a medical

journal, the Food and Drug Administration has required all

bisphosphonate labels to include a precaution, hundreds of lawsuits

have been filed against drug makers, and expert dental groups have

issued advice for managing the tens of millions of people now on the

drugs.

Still, there are no good treatments for what specialists have begun

calling “bisphossy jaw.” Nor is it clear that quitting the drugs

reduces the risk, because bisphosphonates can persist for years in the

bone. The incidence, variation and progression of the jaw disease are

also unclear.

“What we have seen and heard from health-care givers is that more

and more people are showing up with milder forms, so the true incidence

rate now is anybody’s guess,” said John R. Kalmar, an Ohio State

University oral pathologist and author of a May review article in

Annals of Internal Medicine. “We’re telling people to be cautious.”

The advent of bisphosphonates about a decade ago was a boon for

people whose bones were riddled by cancer treatment, osteoporosis, or a

disorder called Paget’s disease. Since 1995, 191 million prescriptions

have been filled for oral Fosamax, Actonel, and Boniva, plus millions

more for intravenous Zometa, Aredia and generic Pamidronate.

However, the benefits and risks of the drugs differ for these patient groups, experts say.

For people with advanced cancer, bisphosphonates can reduce the

painful, crippling damage to bones that can be a side effect of cancer

treatment. But studies suggest that 3 percent to 10 percent of such

patients will develop osteonecrosis of the jaw, both because

intravenous bisphosphonates are so potent and because cancer treatment

itself is a risk factor for bone death.

Novartis, maker of Zometa and Aredia, says it has so far received reports of 2,500 cases of jawbone damage.

“The seriousness… ranges from being asymptomatic to requiring

sections of the jaw to be removed,” Novartis said in a May 2005

informational letter to dentists.

For healthy people seeking to boost bone density, the risk of

jawbone death appears to be remote; the estimate from Fosamax maker

Merck & Co. is less than one out of 100,000 patients per year.

On the other hand, many postmenopausal women taking the pills may

not really need them. Low bone density does not automatically progress

to osteoporosis, and even when it does, a debilitating fracture is not

inevitable.

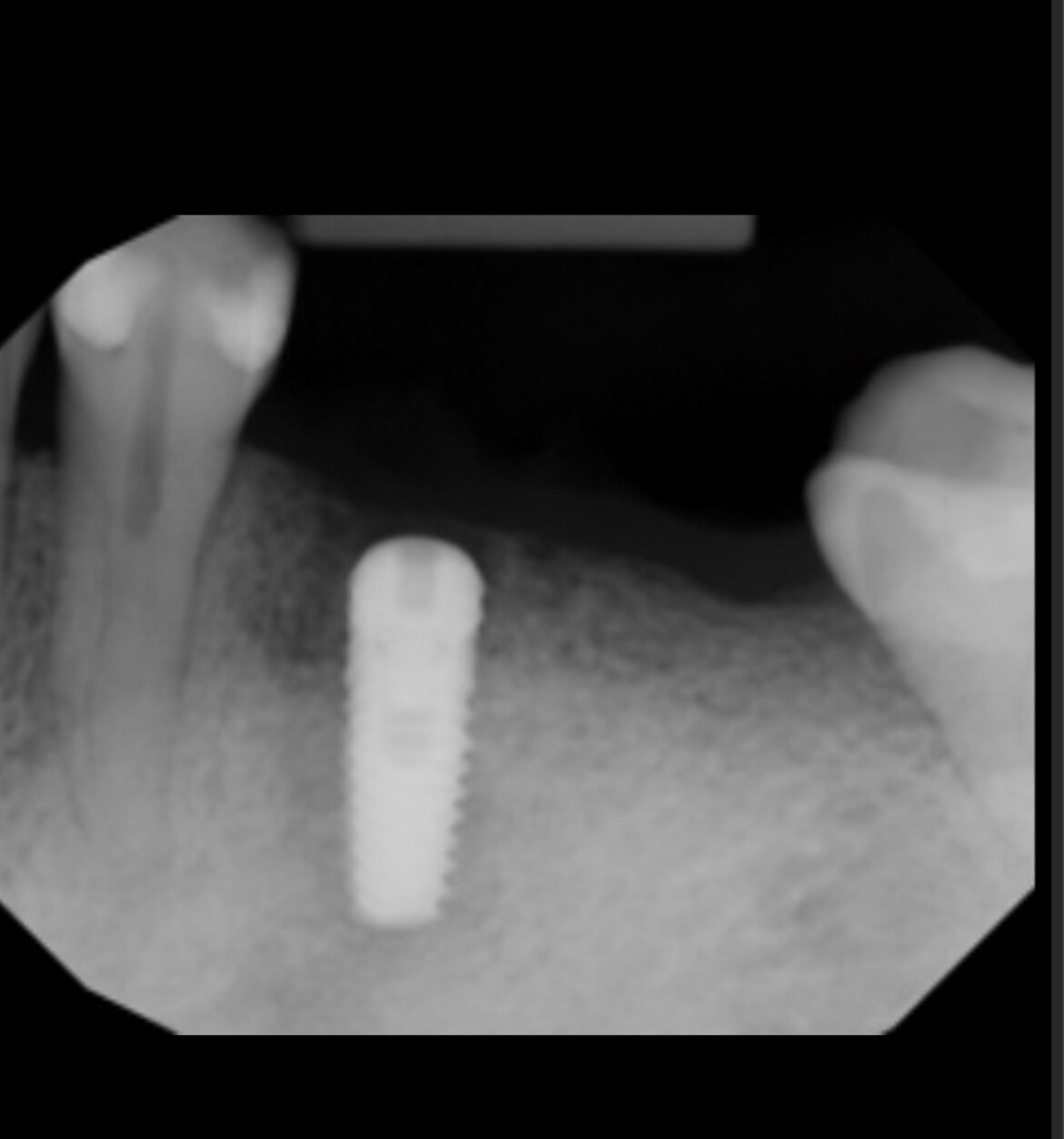

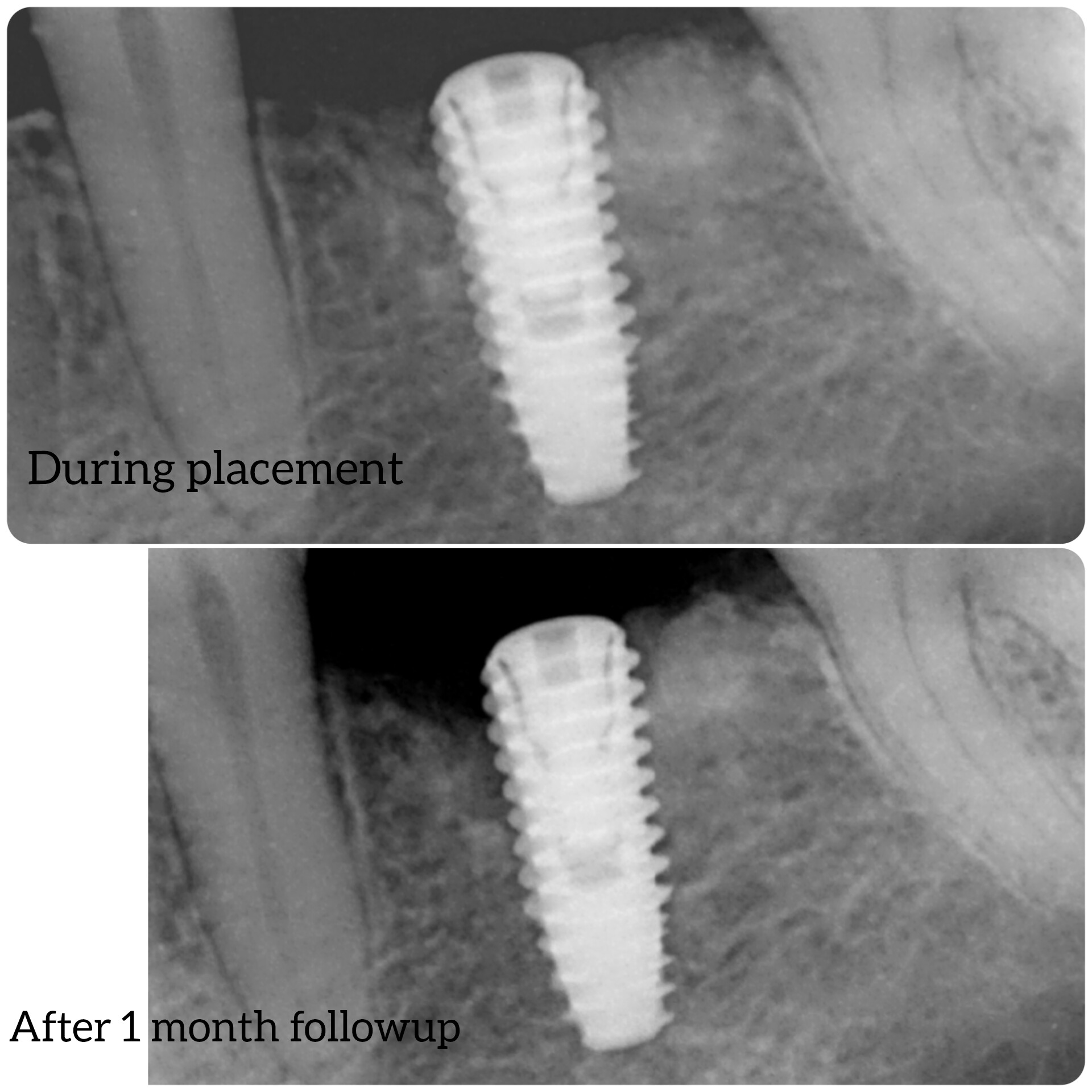

Crystal Baxter, a former University of Pittsburgh professor of

prosthodontics who now practices in Arizona, said she is very leery of

doing elective dental implants in patients who have taken oral

bisphosphonates. “The scary thing,” she said, “is that these drugs are

being marketed to practically every aging woman in the world.”

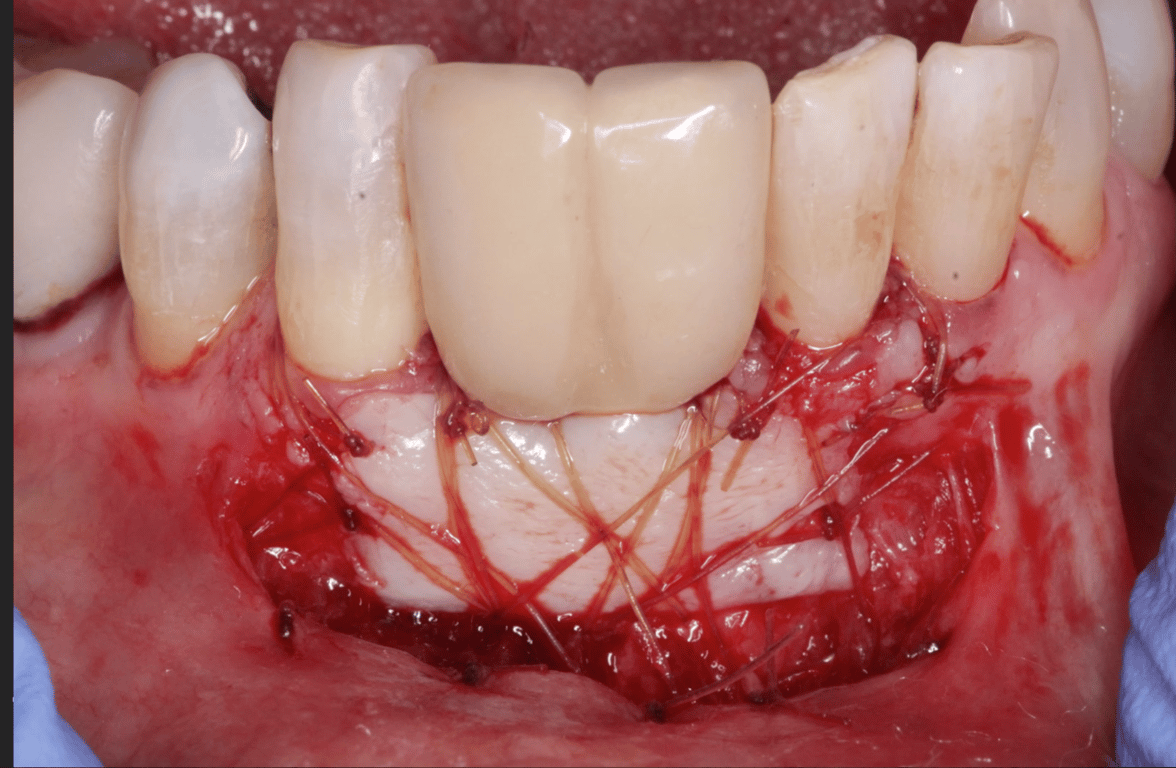

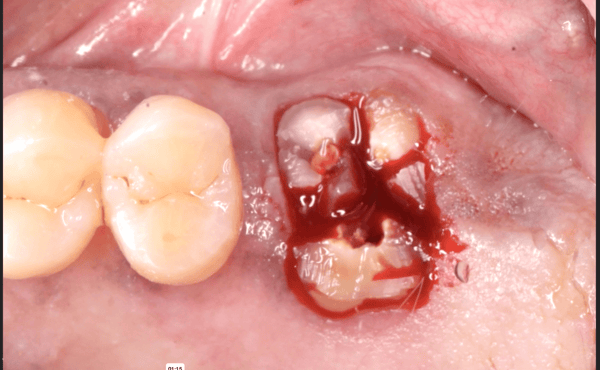

It has become clear – through trial and terrible error – that trying

to fix bisphossy jaw with invasive dental procedures only makes it

worse.

Ruth Ann Dutton, 66, of Atco, for example, went to her regular

dentist after a shard of bone spontaneously broke through her gum.

Although she had taken Aredia and Zometa for advanced breast cancer,

the splintering of her jaw was not triggered by a dental procedure.

“He did a root canal, but it never got better,” she recalled.

A year ago, she was referred to Meltzer, who prescribed antibiotics and antiseptic rinses.

“Right now, it’s doing pretty decent,” she said. “The hole is mostly closed up.”

Barry Levin, an Elkins Park periodontist, said one of his elderly

patients has not been as fortunate. She quit Fosamax after tooth

extractions led to a diagnosis of osteonecrosis, but bone grafted to

her damaged jaw has not healed properly.

“It’s been a nightmare,” Levin said.

Bisphosphonates build bone by tamping down the normal turnover of

bone cells. Kalmar and other experts speculate that osteonecrosis

develops when the drugs are too effective at suppressing bone

regeneration.

Why hasn’t the problem shown up after, say, hip replacement surgery?

Experts say the jaws are particularly vulnerable because cells turn

over faster there than in other bones. Jaws are also constantly exposed

to minor trauma from chewing, and to bacteria from the mouth.

“Unlike the hip, the mouth is not sterile,” said Long Island Medical

Center oral surgeon Salvatore Ruggiero, whose 2004 article on bisphossy

jaw was among the first.

A similar phenomenon, dubbed “phossy jaw,” was recognized in the

mid-1800s among match factory workers who chronically inhaled the

phosphorus on match tips.

“The onset of the disease was generally quite slow, an average of

five years… The lower jaw was more commonly affected than the upper

jaw, exactly as seen in the bisphosphonate-associate osteonecrosis,”

Heiner K. Berthold, a drug expert with the German Medical Association,

wrote this month in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Many patients

committed suicide because of pain and disfigurement.”

Novartis – which received the first report of jaw osteonecrosis in

December 2002 – says it has made public the cases it knows about. It

also enlisted M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Texas to review patient

records and try to gauge the incidence among the 2.8 million patients

treated worldwide with Aredia or Zometa. It has sent letters and

brochures to inform physicians and patients and formed an expert

advisory committee on which Ruggiero sits.

But makers of oral bisphosphonates – Merck, Roche (Boniva) and

Procter & Gamble (Actonel) – have done little to alert patients

other than updating their labels as required by the FDA. Merck has also

put information on its Web site.

These firms stress that in research studies involving tens of

thousands of patients, no cases of jaw osteonecrosis were reported.

More recently, “we have received rare reports,” said Merck spokesman Chris Loder.

Not so quiet are dozens of law firms now seeking injured clients through advertising online and on television and radio.

Advice for Patients

Although osteonecrosis of the jaw is not well understood, the

American Dental Association and other expert groups have issued

recommendations.

Before starting bisphosphonates, have a comprehensive dental exam and treat any tooth or gum problems.

While on bisphosphonates, make sure to brush and floss daily, and

get regular dental care. If you need an invasive dental procedure,

discuss the risks with your doctor. Seek the most conservative possible

treatment. Avoid elective procedures that would require bone to heal.

If dental surgery is necessary, consider taking antibiotics and use daily oral rinses.

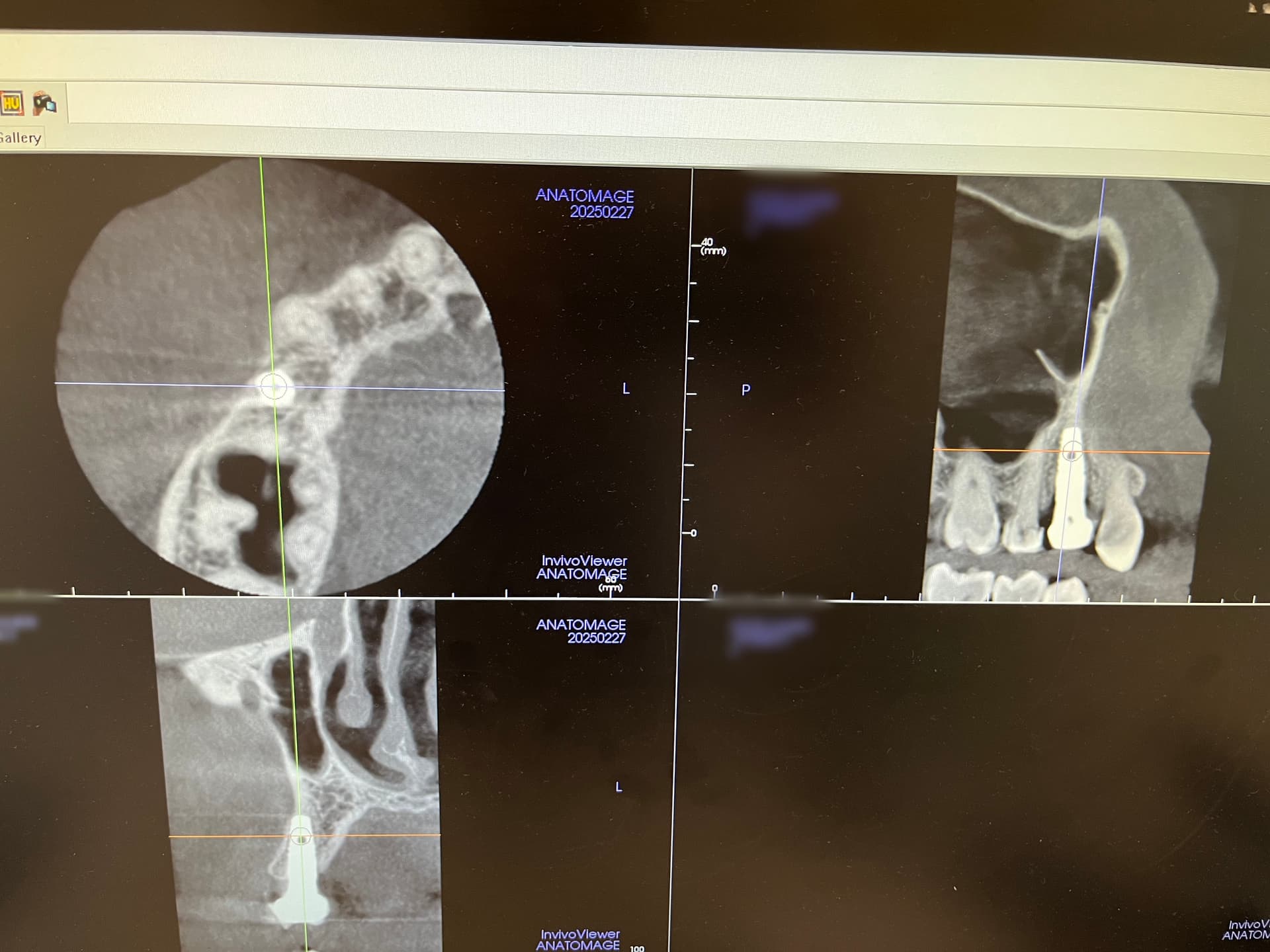

If osteonecrosis develops, special imaging studies, such as computed

tomography scans, may help with diagnosis and treatment. Consider

discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy until the jaw heals. If dead bone

must be removed, it should be done with as little trauma to adjacent

tissues as possible.