Jaw Decay Linked to Fosamax

Source: By Linda Marsa, Special to The LA Times

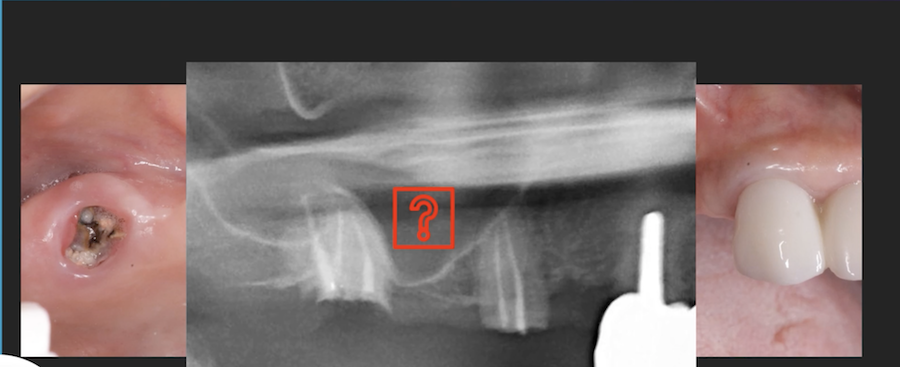

Sue Piervin never suspected the pills she took to strengthen her bones

could severely damage her jaw. Twelve years ago, a routine X-ray

revealed her bones were thinning, so her doctor prescribed a drug to

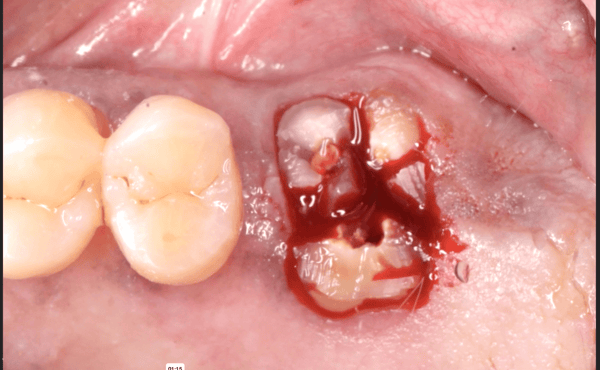

help stop the erosion of bone density. Then, in 1999, Piervin developed

a painful bone spur in her jaw that had decayed to such an extent that

it had to be surgically removed.

At

the time, doctors were puzzled. But when she had a recurrence last

year, they had a pretty good idea what was causing the trouble:

Fosamax, the medication she was taking to prevent bone loss.

Since

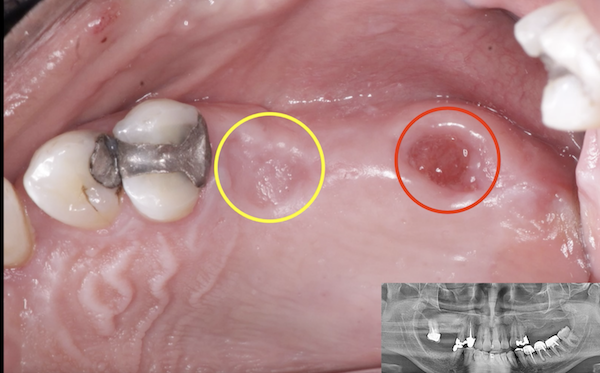

2001, more than 2,400 patients taking Fosamax and other bone-building

medications like it have reported bone death in their jaws, mostly

after a minor trauma such as getting a tooth extracted. Most were

taking especially potent, intravenously delivered versions of these

drugs, which are known as bisphosphonates.

An additional 120

people who were taking bisphosphonates in pill form to prevent bone

thinning have been stricken with such incapacitating bone, joint or

muscle pain that some were bedridden and others required walkers,

crutches or wheelchairs.

The incidence of both these

complications is minuscule in comparison with the millions of people

taking these medications. More than 36 million prescriptions for oral

bisphosphonates, such as Actonel, Fosamax and Boniva, were dispensed in

2005, according to IMS Health, a pharmaceutical information and

consulting company. Nearly 3 million cancer patients have been treated

with intravenous versions of the medications.

But because at

least 90% of drug side effects aren’t reported to the Food and Drug

Administration, the real number of people stricken with jaw necrosis

and other side effects could be higher.

"We’ve uncovered about

1,000 patients [with jaw necrosis] in the past six to nine months

alone, so the magnitude of the problem is just starting to be

recognized," says Kenneth M. Hargreaves, chair of the endodontics

department at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San

Antonio.

With concern growing over the possible side effect, the

American Assn. of Endodontists last week released a position statement

on the problem. "Until further information is available, it would

appear prudent to consider all patients taking bisphosphonates to be at

some risk," the group said.

Unreported cases of the pain

syndrome may be "considerable," says Diane K. Wysowski of the FDA’s

Office of Drug Safety, "because physicians may attribute the pain to

osteoporosis."

The issue is especially worrisome, says Dr. Susan

M. Ott, an osteoporosis expert at the University of Washington in

Seattle, because the number of women taking bisphosphonates stands to

increase now that women are more reluctant to preserve their bones by

taking estrogen after menopause.

In 2002, when a landmark study

revealed that hormone replacement therapy carried slight but measurable

heart and breast cancer risks, prescriptions for oral bisphosphonates

shot up 32%, according to IMS Health.

Bisphosphonate drugs

have been used since 1995 to strengthen bone in women who are losing

bone density and for nearly 15 years in men and women who have cancer.

The medicines act by altering the dynamics of bone, which is constantly

being turned over.

Cells called osteoclasts break bone down.

Others called osteoblasts build it up. Osteoporosis occurs when

formation of new bone does not keep pace with bone destruction.

Debate over risks

Bisphosphonates

thwart the action of the osteoclasts, thickening bones and making them

less likely to break. Physicians aren’t sure why these drugs sometimes

do seemingly the opposite and cause jaw death. But they know that

osteoclasts are also involved in prompting osteoblasts to form.

Consequently, over time, these medications may actually impede rather

than promote the creation of new bone.

Christopher Loder, a

spokesman for Fosamax maker Merck, points out that osteonecrosis of the

jaw with Fosamax is "exceedingly rare." "In all of our controlled

clinical trials with Fosamax, which involved more than 17,000 patients,

including some that were 10 years in duration, we had no reports" of

it, he says.

The risk appears to vary according to the strength

of the bisphosphonate being used. Recent studies show that about 80% to

90% of jaw decay occurs in cancer patients who take potent intravenous

bisphosphonates (Aredia, Zometa). The drugs replenish bone tissue that

is lost when cancer spreads to the bone and can reduce pain and the

risk of debilitating fractures.

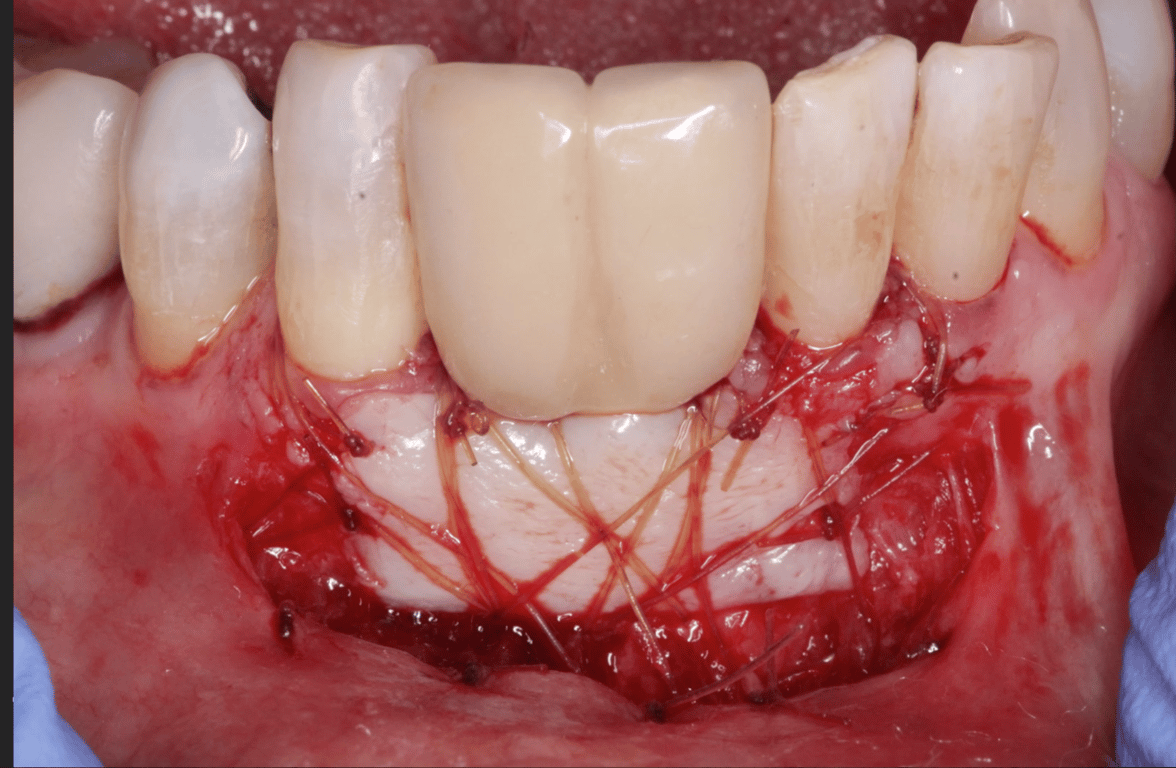

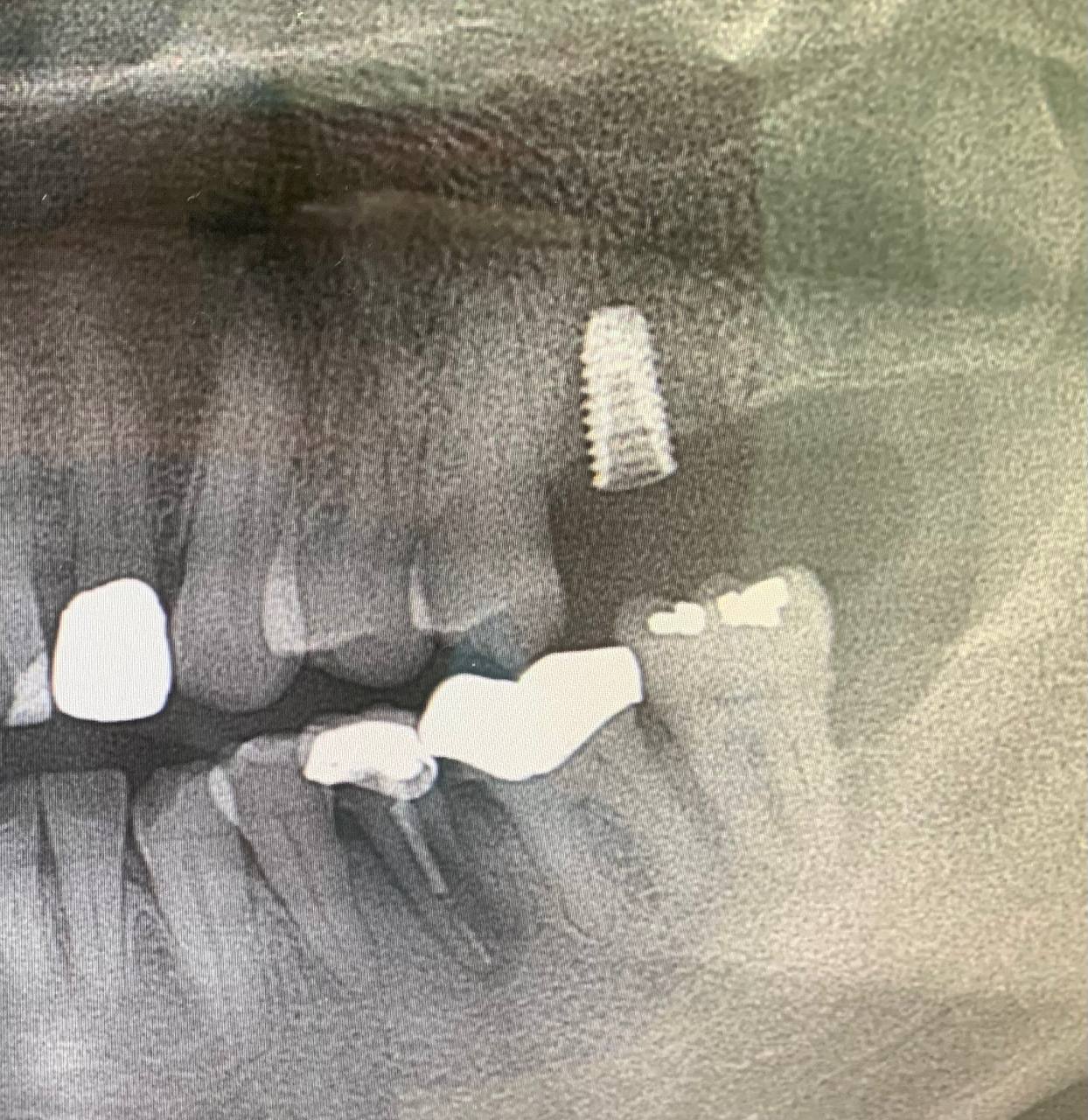

The rare side effect, called

osteonecrosis of the jaw, causes severe infections, swelling and the

loosening of teeth. Patients often require long-term antibiotic therapy

or surgery to remove the dying bone tissue.

"I’ve taken off

several jaws because of this problem," says Dr. Salvatore Ruggiero, an

oral surgeon at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New York who was

among the first to observe this phenomenon in 2001. "Because bone death

can’t be reversed, there’s nothing we can do for these patients except

ease their pain and prevent it from spreading."

Patients who

have cancer-related bone weakening and pain have few options but to

take bisphosphonates. More worrisome for experts are the millions of

women such as Piervin who take the weaker bisphosphonate pills to treat

osteoporosis, and for many more years than do cancer patients. "Even

though the chances of getting this are small, considering there are 23

million women taking this drug, we could be talking about a significant

number of people," Ruggiero says. "Risks increase the longer you’re on

the drugs, and it can take years for the complication to manifest

itself."

It’s not uncommon for rare side effects to come to

light only after a drug has been approved, says Dr. Eric Colman of the

FDA’s Division of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs in Silver Spring, Md.

Serious adverse reactions that weren’t apparent in premarket tests

emerge in half of all prescription medications.

"People need to realize there are unknown side effects with every drug, and these medications are no exception," he says**.**

What patients can do

In

the last two years, drug makers have added warnings about bone death to

some of the medications’ labels and about the pain syndrome to all of

them.

But despite an alert sent to physicians by the FDA in

2004, "it’s been a battle getting people educated," Ruggiero says.

Dentists and oncologists know about the problem, but gynecologists and

family doctors, who write many of the prescriptions for oral

bisphosphonates, aren’t as informed.

Patients

need to be vigilant. "Women taking these drugs for osteoporosis should

tell their doctor if they develop severe pain," says Dr. Theresa Kehoe,

an endocrinologist with the FDA’s Division of Endocrine and Metabolic

Drugs.

In addition, anyone who uses oral or intravenous

bisphosphonates should alert their dentist and oral surgeon if they

need an invasive dental procedure. Better yet, says Hargreaves, get

dental work done before going on these drugs, although avoiding jaw

trauma is no guarantee of protection.

The drugs greatly reduce

risks of incapacitating fractures for older women with osteoporosis.

Women who don’t have osteoporosis but have other risk factors, such as

usage of bone-depleting steroids, previous fractures or a family

history of the condition can also benefit, says Dr. Charles H. Chestnut

III, who heads osteoporosis research at the University of Washington.

But

they should be considered far more cautiously by younger women who have

less bone thinning and are taking oral bisphosphonates simply to

prevent further deterioration. These meds become incorporated into the

bone’s matrix, where they can linger for five years or more. Their

effects are cumulative. And women are expected to take them for the

rest of their lives.

"These drugs are still relatively new and problems sometimes take years to show up," says Ott of the University of Washington.

"We’re

not quite sure what we’re dealing with over the long haul. Side effects

like this should make ordinary, healthy women think twice."

Piervin

still takes calcium and Miacalcin, a nasal spray that helps preserve

bone density but isn’t nearly as potent as the bisphosphonates. She

also walks every day and does weight-bearing exercise three times

weekly to help her bones stay stronger — even parks her car eight to 10

blocks from work to fit more walking into her schedule.

She’d take hormones, but she’s worried about the risk. She’d exercise more, but she doesn’t have the time.

"I’m off Fosamax," she says, "but I’m in limbo regarding future treatment."