The Academic Who Went to Market

Source: financialexpress-bd.com, Henry Tricks

An inspiring story of an academic, that developed a technique for measuring implant performance, and in 1998 founded a spin-off company with Imperial College London to exploit the idea commercially.

A decade ago, Neil Meredith believes, it would have been impossible to build the multinational business he has created in five years from a desktop computer on his kitchen table. His tiny product — smaller than a rawlplug — includes titanium parts produced in Scandinavia, gold parts manufactured in Switzerland and stainless steel parts made in Germany. His business partner, Fredrik Engman, lives in Sweden. Their main market is Germany, but the head office is in Harrogate, Yorkshire. On paper, it looks like a European Union (EU) bureaucrat’s fantasy company but Neoss’s products are as flesh and bone as they come.

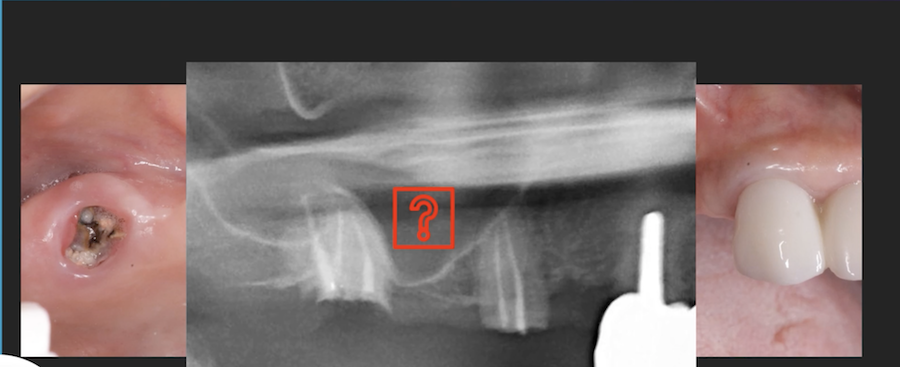

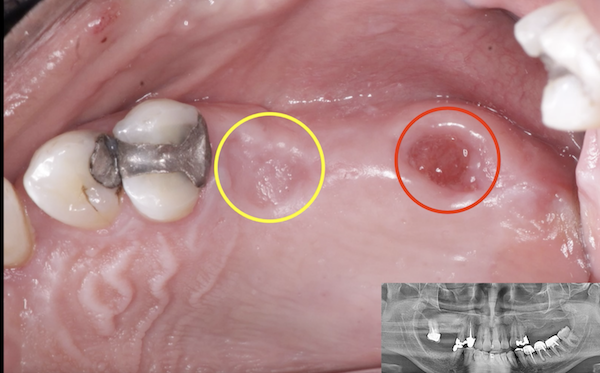

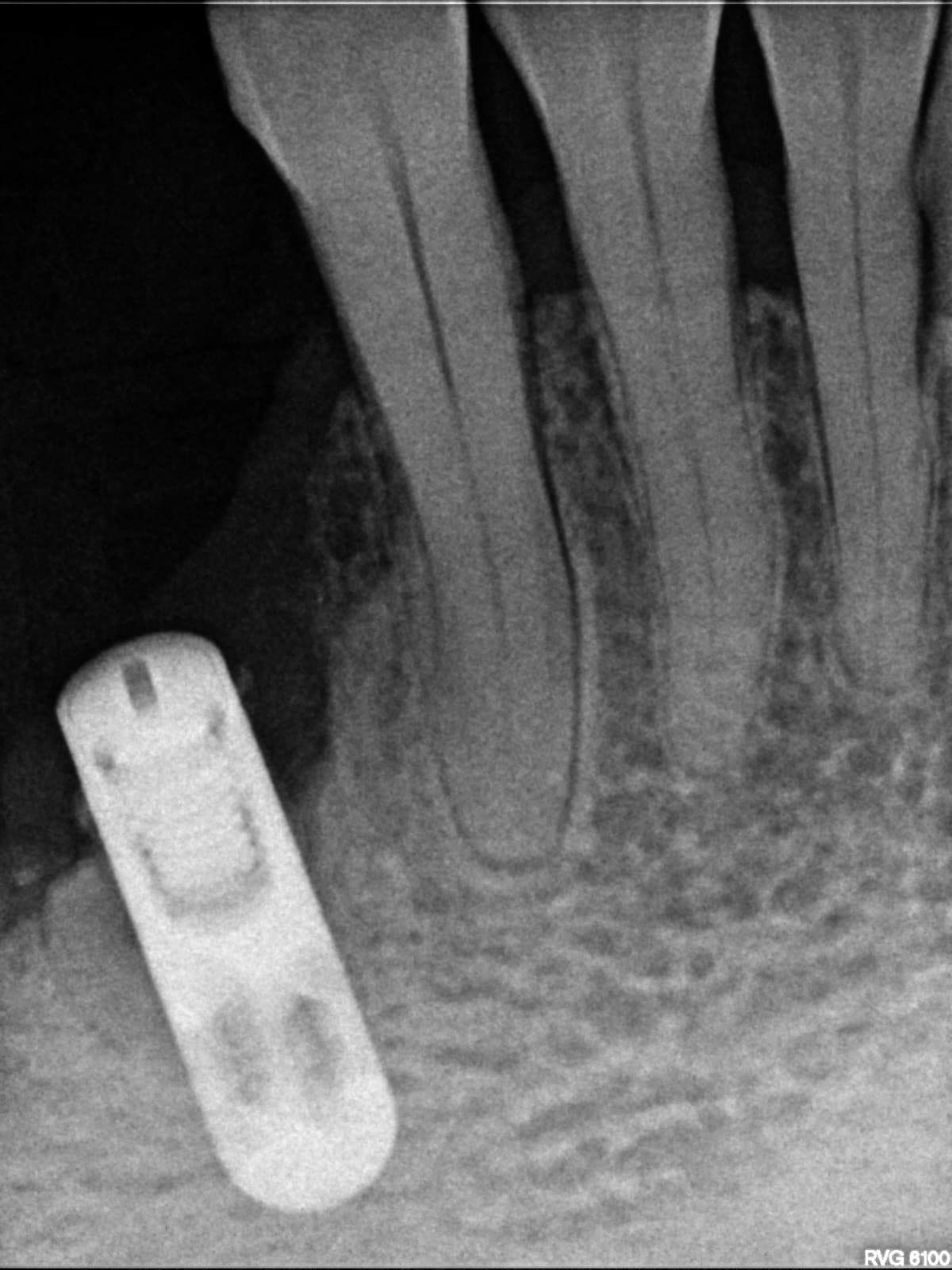

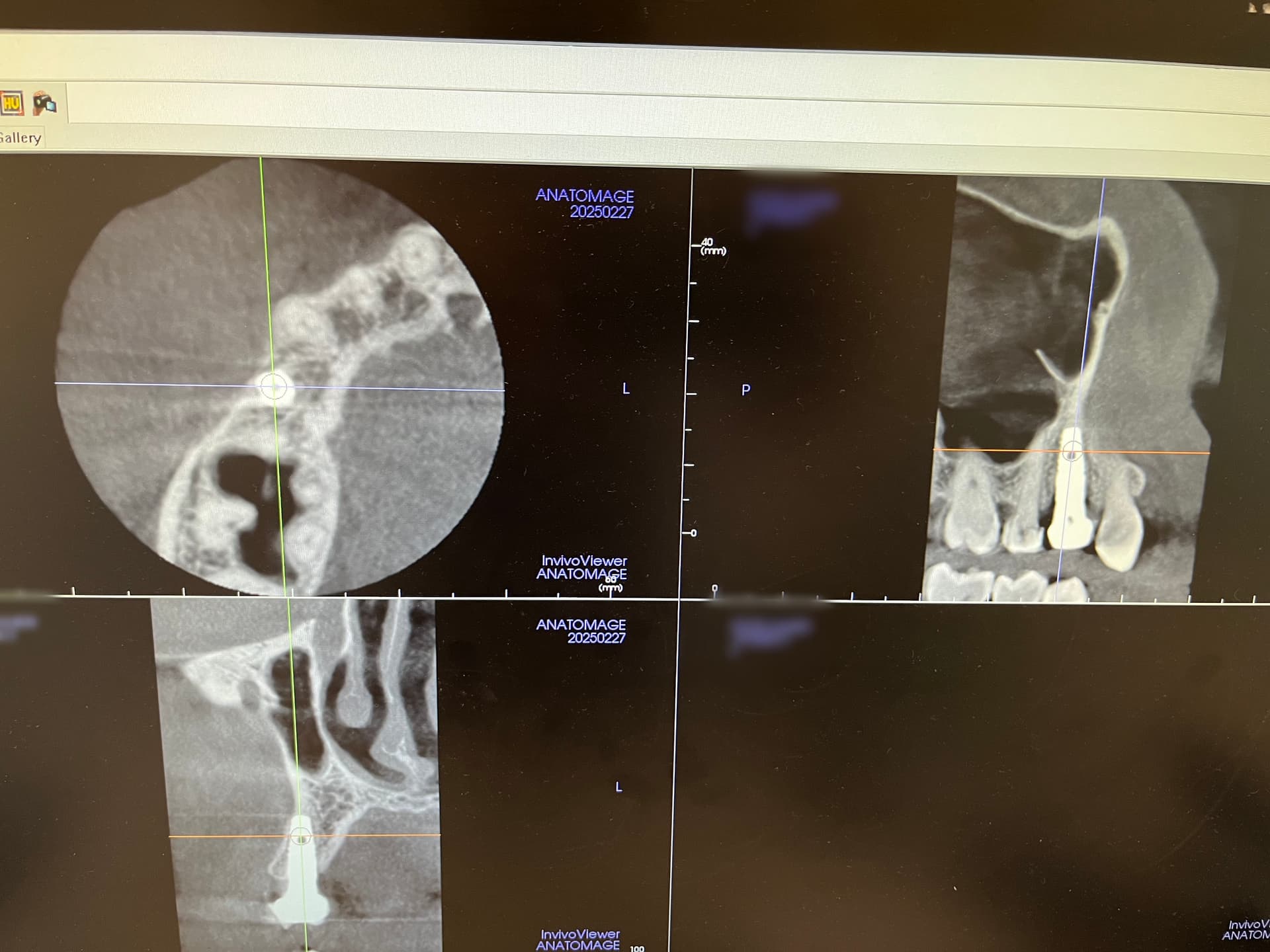

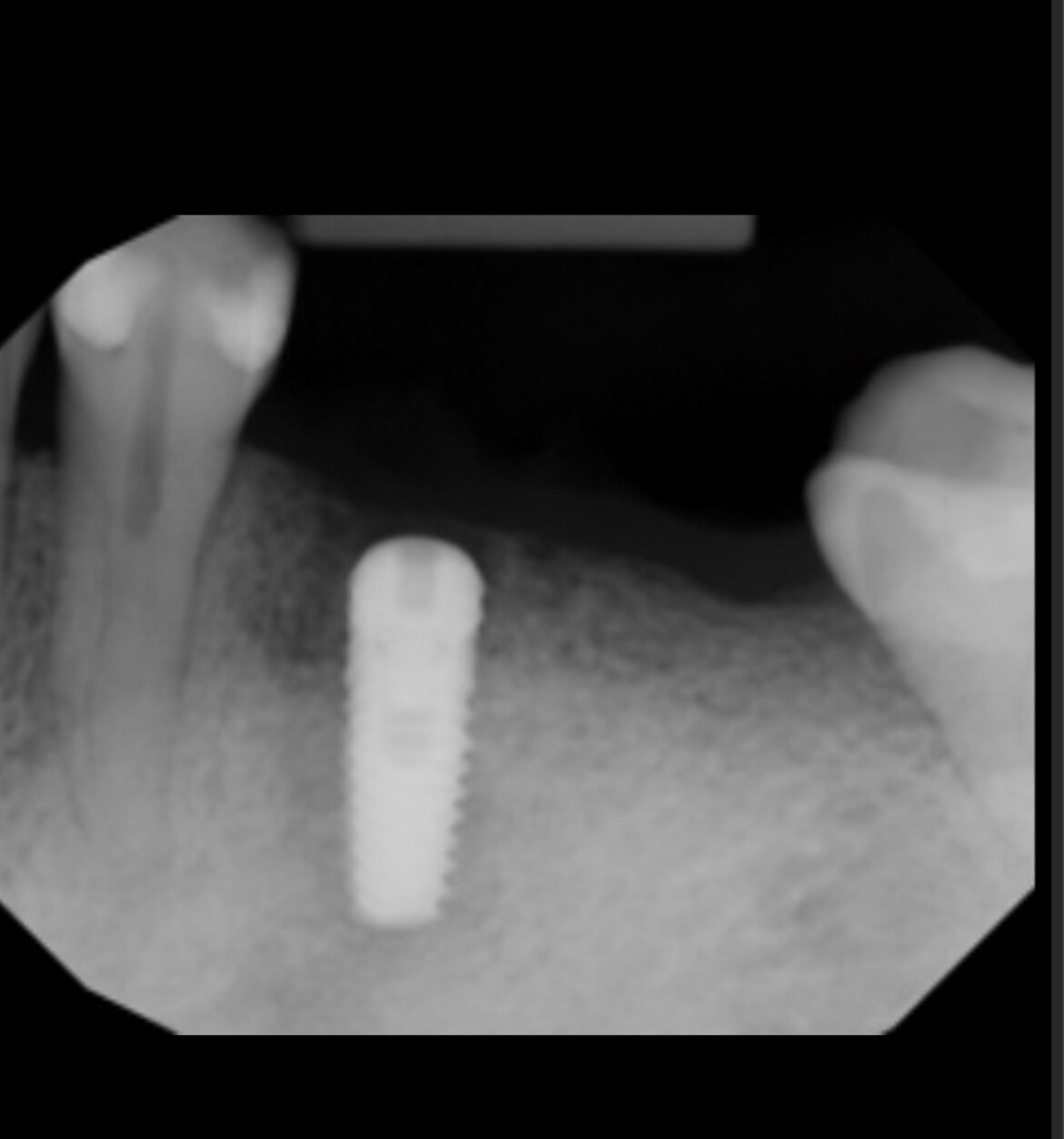

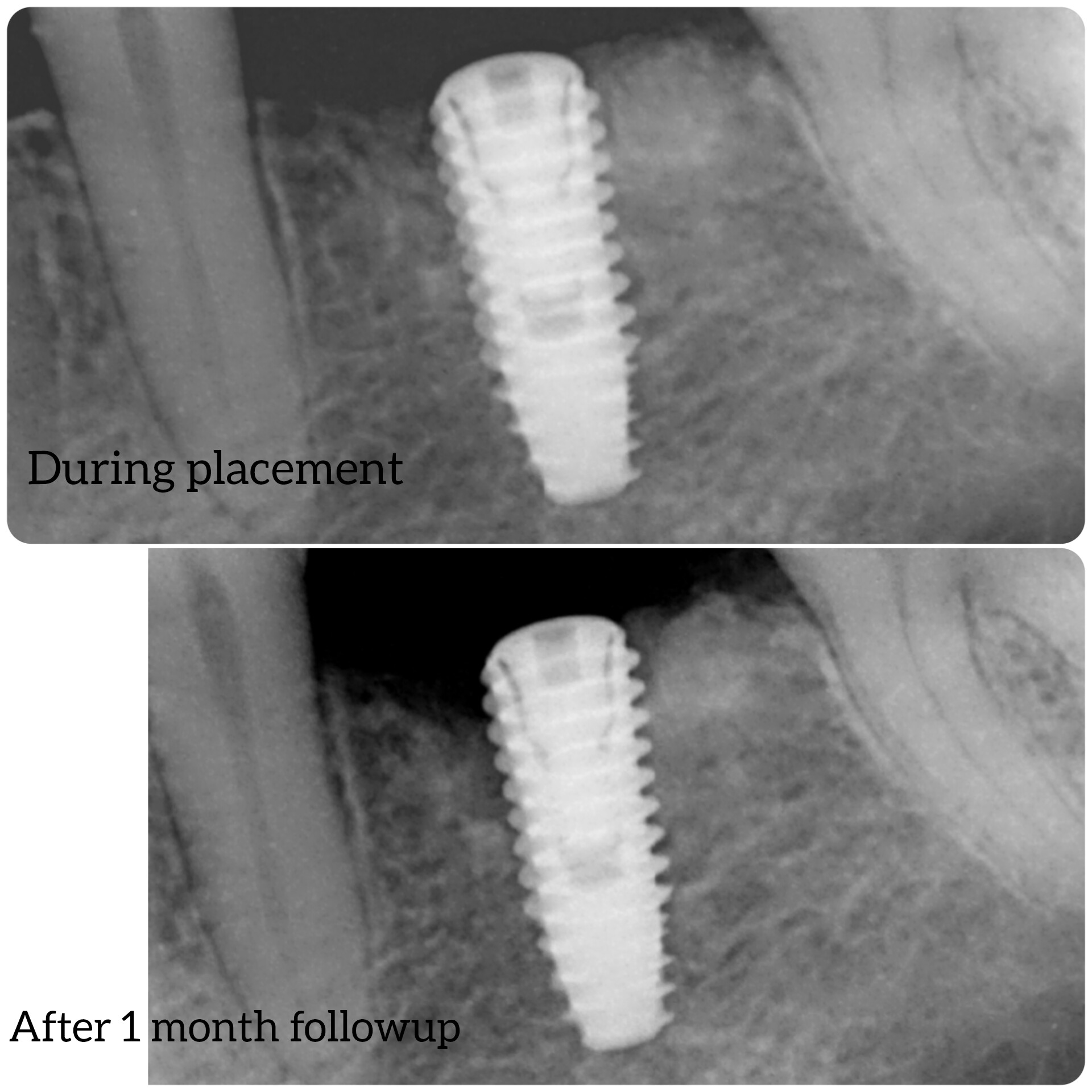

They are implants that dentists drill into jawbones, on to which are screwed the crowns and bridges that most people are forced to endure at some time in their life, especially as they get older.It is estimated to be a $1.5bn-$2.0bn (£850m-£1.13bn) market, dominated by two heavyweights, Nobel Biocare of Sweden and Straumann of Switzerland. According to Goldman Sachs, it has expanded between 15 and 20 per cent recently.

So how has the 46-year-old British academic, who is visiting professor in dentistry at Bristol University and still practises as an implant specialist once a fortnight, muscled into such competitive territory?

Mr Meredith is a rare breed of academic who can take his ideas from the drawing board and into the market. As an academic, he developed a technique for measuring implant performance, and in 1998 he founded a spin-off company with Imperial College London to exploit the idea commercially. Two years later, he began experimenting by e-mail with Mr Engman on ways to simplify dental implants.He and Mr Engman, a dental implant innovator who had previously worked at Nobel Biocare, had collaborated before and were suited to doing business together. Their strengths offset each others’ weaknesses, he says.

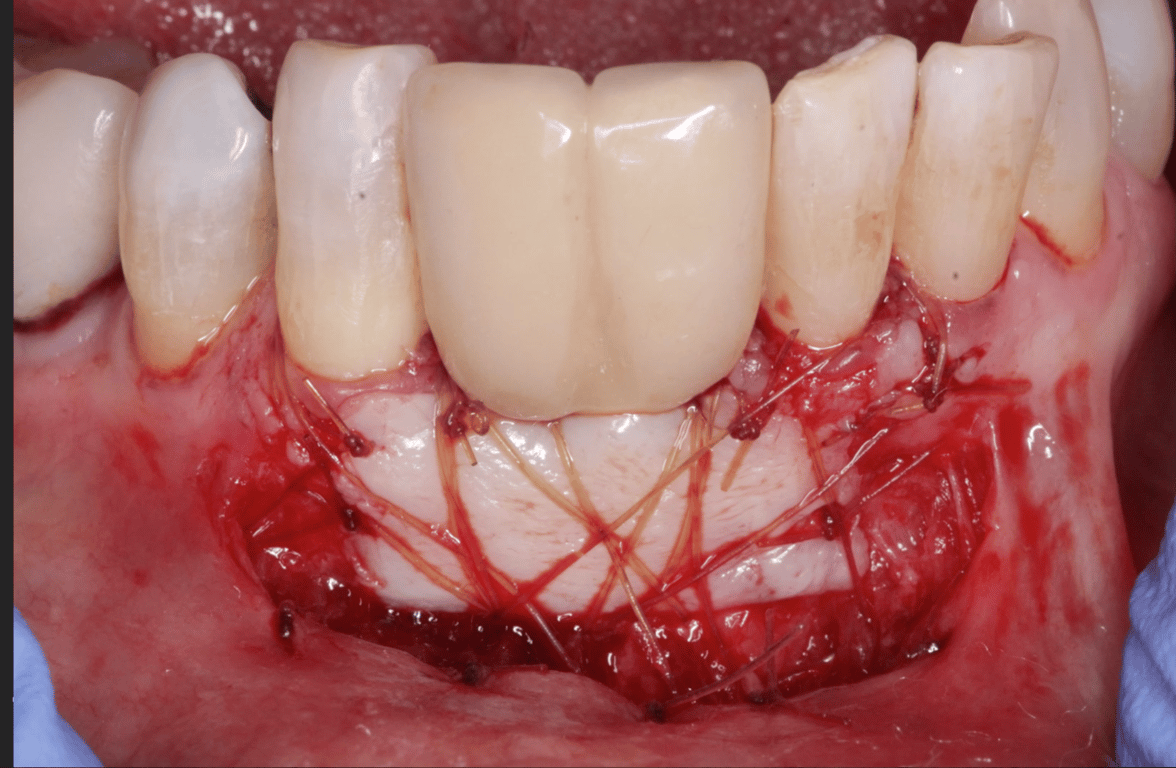

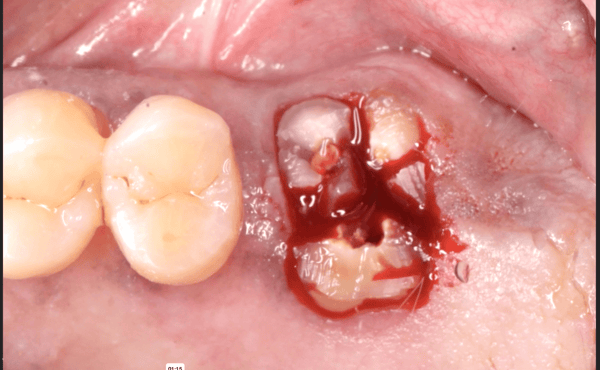

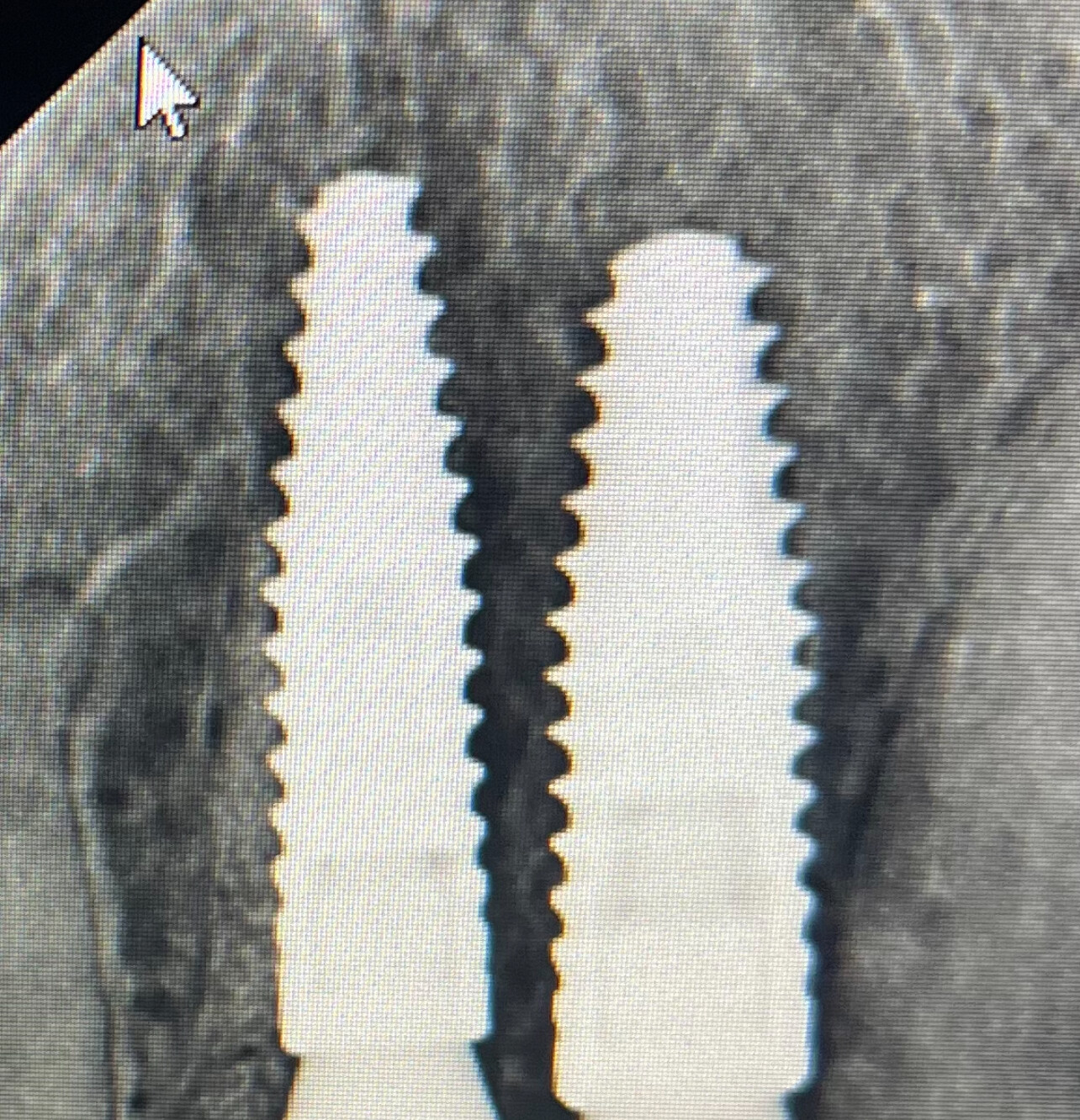

They were not the only specialists who saw the need for a better implant — but they acted upon their curiosity. “A lot of people had the idea that something needed to be done. Fredrik and I sat down and did it,” he says. Together, they designed an implant whose main virtue was simplicity.They engineered a single product that can embed itself in bone that, Mr Meredith says, can range from “as hard as teak to as soft as balsa wood” in the same mouth. He argues that other manufacturers have different implants for different types of bone, each with thousands of components. His has 100 and is small enough to be put in an envelope and couriered round the world.

After designing the product, the first challenge was persuading prototype manufacturers to take the idea seriously. Because Mr Meredith was a well-known academic and Mr Engman a proven technician, that was not as hard as it might have been. Then they tested the prototype by setting the hurdles high. They tested in Switzerland, a country where dentists have good technical knowledge and can explain their likes and dislikes lucidly. Mr Meredith gives the impression that the pair never scrimped on testing and genuinely welcomed feedback — all with the goal of improving quality.

The seed capital up to this point was just £150,000. Egged on by colleagues, they decided to commercialise their idea. Mr Meredith says it was not easy to find venture capital funding, especially after the dotcom crash.He says also that venture capitalists tend to be wary of inventors because they often lack commercial sense. But after some months, Neoss found two VC partners, MMC Ventures and Delta Partners. MMC says it was impressed by the expertise of those involved and the prototype product, which was “beautifully engineered”. They stumped up £1.0m.

But even with that money, Neoss remained “parsimonious,” Mr Meredith says. It started with three staff and only recruited as the business expanded. The venture capitalists provided business expertise, including a former McKinsey consultant working with MMC who provided free advice. Neoss also used northern lawyers and accountants who made “virtual investments” in the business they charged low fees but these rose with Neoss. Mr Meredith and Mr Engman worked tirelessly with little financial reward. “There’s a lot of sweated equity in this,” Mr Meredith says.

Sales began two years ago, focused on Germany, where the dental implant market is Europe’s biggest — seven times the size of the UK market. Sales are rising at 200 per cent annually, he says, and within a year Neoss had a one per cent market share in Germany. It has won approval to enter the US market but Mr Meredith is wary of overexpansion. “It would appear sensible to go deeper into fewer markets, because that way you can manage your resources more carefully,” he reasons. This means keeping all stock in the UK to keep close tabs on it, and getting to grips with the vagaries of working capital management in key markets. Germans, for example, pay by direct debit two days after being invoiced. Italians may take months, he says.

His VC partners have a five- to seven-year window before exiting and he too sees enough excitement in the business to stay put for now. He says: “VCs tend to be quite sensitive about academic founders. But thankfully they aren’t looking to replace me.”